Homework 3: Trees, Data Abstraction

Due by 11:59pm on Thursday, October 8

查看汉语翻译

Instructions

Download hw03.zip. Inside the archive, you will find a file called

hw03.py, along with a copy of the ok autograder.

Submission: When you are done, submit with python3 ok

--submit. You may submit more than once before the deadline; only the

final submission will be scored. Check that you have successfully submitted

your code on okpy.org. See Lab

0 for more instructions on

submitting assignments.

Using Ok: If you have any questions about using Ok, please refer to this guide.

Readings: You might find the following references useful:

Grading: Homework is graded based on correctness. Each incorrect problem will decrease the total score by one point. There is a homework recovery policy as stated in the syllabus. This homework is out of 2 points.

Required questions

Watch the hints video below for somewhere to start:

Abstraction

Mobiles

Acknowledgements. This mobile example is based on a classic problem from MIT Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, Section 2.2.2.

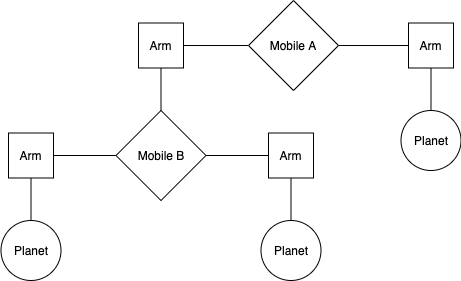

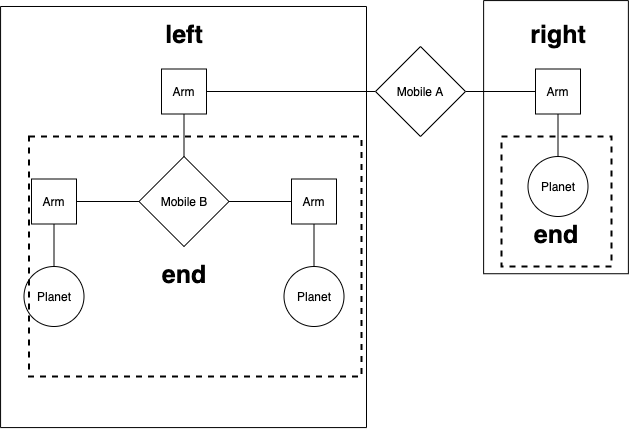

We are making a planetarium mobile. A mobile is a type of hanging sculpture. A binary mobile consists of two arms. Each arm is a rod of a certain length, from which hangs either a planet or another mobile. For example, the below diagram shows the left and right arms of Mobile A, and what hangs at the ends of each of those arms.

We will represent a binary mobile using the data abstractions below.

- A

mobilemust have both a leftarmand a rightarm. - An

armhas a positive length and must have something hanging at the end, either amobileorplanet. - A

planethas a positive size, and nothing hanging from it.

Arms-length recursion (sidenote)

Before we get started, a quick comment on recursion with tree data structures. Consider the following function.

def min_depth(t):

"""A simple function to return the distance between t's root and its closest leaf"""

if is_leaf(t):

return 0 # Base case---the distance between a node and itself is zero

h = float('inf') # Python's version of infinity

for b in branches(t):

if is_leaf(b): return 1 # !!!

h = min(h, 1 + min_depth(b))

return hThe line flagged with !!! is an "arms-length" recursion violation. Although our code works

correctly when it is present, by performing this check we are doing work that should be done by the next level

of recursion—we already have an if-statement that handles any inputs to min_depth that are

leaves, so we should not include this line to eliminate redundancy in our code.

def min_depth(t):

"""A simple function to return the distance between t's root and its closest leaf"""

if is_leaf(t):

return 0

h = float('inf')

for b in branches(t):

# Still works fine!

h = min(h, 1 + min_depth(b))

return hArms-length recursion is not only redundant but often complicates our code and obscures the functionality of recursive functions, making writing recursive functions much more difficult. We always want our recursive case to be handling one and only one recursive level. We may or may not be checking your code periodically for things like this.

Q1: Weights

Implement the planet data abstraction by completing the planet constructor

and the size selector so that a planet is represented using a two-element list

where the first element is the string 'planet' and the second element is its size.

The total_weight example is provided to demonstrate use of the mobile, arm,

and planet abstractions.

def mobile(left, right):

"""Construct a mobile from a left arm and a right arm."""

assert is_arm(left), "left must be a arm"

assert is_arm(right), "right must be a arm"

return ['mobile', left, right]

def is_mobile(m):

"""Return whether m is a mobile."""

return type(m) == list and len(m) == 3 and m[0] == 'mobile'

def left(m):

"""Select the left arm of a mobile."""

assert is_mobile(m), "must call left on a mobile"

return m[1]

def right(m):

"""Select the right arm of a mobile."""

assert is_mobile(m), "must call right on a mobile"

return m[2]def arm(length, mobile_or_planet):

"""Construct a arm: a length of rod with a mobile or planet at the end."""

assert is_mobile(mobile_or_planet) or is_planet(mobile_or_planet)

return ['arm', length, mobile_or_planet]

def is_arm(s):

"""Return whether s is a arm."""

return type(s) == list and len(s) == 3 and s[0] == 'arm'

def length(s):

"""Select the length of a arm."""

assert is_arm(s), "must call length on a arm"

return s[1]

def end(s):

"""Select the mobile or planet hanging at the end of a arm."""

assert is_arm(s), "must call end on a arm"

return s[2]def planet(size):

"""Construct a planet of some size."""

assert size > 0

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

def size(w):

"""Select the size of a planet."""

assert is_planet(w), 'must call size on a planet'

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

def is_planet(w):

"""Whether w is a planet."""

return type(w) == list and len(w) == 2 and w[0] == 'planet'def total_weight(m):

"""Return the total weight of m, a planet or mobile.

>>> t, u, v = examples()

>>> total_weight(t)

3

>>> total_weight(u)

6

>>> total_weight(v)

9

>>> from construct_check import check

>>> # checking for abstraction barrier violations by banning indexing

>>> check(HW_SOURCE_FILE, 'total_weight', ['Index'])

True

"""

if is_planet(m):

return size(m)

else:

assert is_mobile(m), "must get total weight of a mobile or a planet"

return total_weight(end(left(m))) + total_weight(end(right(m)))Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q total_weightQ2: Balanced

Implement the balanced function, which returns whether m is a balanced

mobile. A mobile is balanced if two conditions are met:

- The torque applied by its left arm is equal to that applied by its right

arm. The torque of the left arm is the length of the left rod multiplied by the

total weight hanging from that rod. Likewise for the right. For example,

if the left arm has a length of

5, and there is amobilehanging at the end of the left arm of weight10, the torque on the left side of our mobile is50. - Each of the mobiles hanging at the end of its arms is balanced.

Planets themselves are balanced, as there is nothing hanging off of them.

def balanced(m):

"""Return whether m is balanced.

>>> t, u, v = examples()

>>> balanced(t)

True

>>> balanced(v)

True

>>> w = mobile(arm(3, t), arm(2, u))

>>> balanced(w)

False

>>> balanced(mobile(arm(1, v), arm(1, w)))

False

>>> balanced(mobile(arm(1, w), arm(1, v)))

False

>>> from construct_check import check

>>> # checking for abstraction barrier violations by banning indexing

>>> check(HW_SOURCE_FILE, 'balanced', ['Index'])

True

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q balancedQ3: Totals

Implement totals_tree, which takes a mobile (or planet) and returns a

tree whose root is the total weight of the input. For a planet,

totals_tree

should return a leaf. For a mobile, totals_tree should return a tree whose

label is that mobile's total weight, and whose branches are totals_trees for the

ends of its arms.

def totals_tree(m):

"""Return a tree representing the mobile with its total weight at the root.

>>> t, u, v = examples()

>>> print_tree(totals_tree(t))

3

2

1

>>> print_tree(totals_tree(u))

6

1

5

3

2

>>> print_tree(totals_tree(v))

9

3

2

1

6

1

5

3

2

>>> from construct_check import check

>>> # checking for abstraction barrier violations by banning indexing

>>> check(HW_SOURCE_FILE, 'totals_tree', ['Index'])

True

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q totals_treeTrees

Q4: Replace Leaf

Define replace_leaf, which takes a tree t, a value find_value, and a

value

replace_value. replace_leaf returns a new tree that's the same as t

except

that every leaf label equal to find_value has been replaced with replace_value.

def replace_leaf(t, find_value, replace_value):

"""Returns a new tree where every leaf value equal to find_value has

been replaced with replace_value.

>>> yggdrasil = tree('odin',

... [tree('balder',

... [tree('thor'),

... tree('freya')]),

... tree('frigg',

... [tree('thor')]),

... tree('thor',

... [tree('sif'),

... tree('thor')]),

... tree('thor')])

>>> laerad = copy_tree(yggdrasil) # copy yggdrasil for testing purposes

>>> print_tree(replace_leaf(yggdrasil, 'thor', 'freya'))

odin

balder

freya

freya

frigg

freya

thor

sif

freya

freya

>>> laerad == yggdrasil # Make sure original tree is unmodified

True

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q replace_leafQ5: Preorder

Define the function preorder, which takes in a tree as an argument and

returns a list of all the entries in the tree in the order that

print_tree would print them.

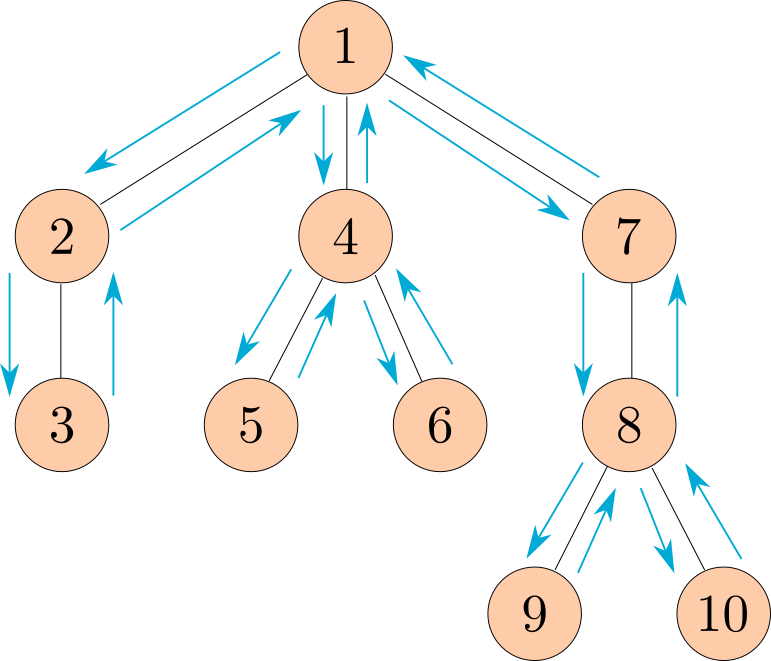

The following diagram shows the order that the nodes would get printed, with the arrows representing function calls.

Note: This ordering of the nodes in a tree is called a preorder traversal.

def preorder(t):

"""Return a list of the entries in this tree in the order that they

would be visited by a preorder traversal (see problem description).

>>> numbers = tree(1, [tree(2), tree(3, [tree(4), tree(5)]), tree(6, [tree(7)])])

>>> preorder(numbers)

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

>>> preorder(tree(2, [tree(4, [tree(6)])]))

[2, 4, 6]

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q preorderQ6: Has Path

Write a function has_path that takes in a tree t and a string word. It

returns True if there is a path that starts from the root where the entries

along the path spell out the word, and False otherwise. (This data structure

is called a trie, and it has a lot of cool applications!---think autocomplete). You

may assume that every node's label is exactly one character.

def has_path(t, word):

"""Return whether there is a path in a tree where the entries along the path

spell out a particular word.

>>> greetings = tree('h', [tree('i'),

... tree('e', [tree('l', [tree('l', [tree('o')])]),

... tree('y')])])

>>> print_tree(greetings)

h

i

e

l

l

o

y

>>> has_path(greetings, 'h')

True

>>> has_path(greetings, 'i')

False

>>> has_path(greetings, 'hi')

True

>>> has_path(greetings, 'hello')

True

>>> has_path(greetings, 'hey')

True

>>> has_path(greetings, 'bye')

False

"""

assert len(word) > 0, 'no path for empty word.'

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q has_pathSubmit

Make sure to submit this assignment by running:

python3 ok --submitExtra Questions

Q7: Interval Abstraction

Alyssa's program is incomplete because she has not specified the implementation of the interval abstraction. She has implemented the constructor for you; fill in the implementation of the selectors.

def interval(a, b):

"""Construct an interval from a to b."""

return [a, b]

def lower_bound(x):

"""Return the lower bound of interval x."""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

def upper_bound(x):

"""Return the upper bound of interval x."""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to unlock and test your code:

python3 ok -q interval -u

python3 ok -q intervalLouis Reasoner has also provided an implementation of interval multiplication. Beware: there are some data abstraction violations, so help him fix his code before someone sets it on fire: https://youtu.be/QwoghxwETng

def mul_interval(x, y):

"""Return the interval that contains the product of any value in x and any

value in y."""

p1 = x[0] * y[0]

p2 = x[0] * y[1]

p3 = x[1] * y[0]

p4 = x[1] * y[1]

return [min(p1, p2, p3, p4), max(p1, p2, p3, p4)]Use Ok to unlock and test your code:

python3 ok -q mul_interval -u

python3 ok -q mul_intervalQ8: Sub Interval

Using reasoning analogous to Alyssa's, define a subtraction function for intervals. Try to reuse functions that have already been implemented if you find yourself repeating code.

def sub_interval(x, y):

"""Return the interval that contains the difference between any value in x

and any value in y."""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to unlock and test your code:

python3 ok -q sub_interval -u

python3 ok -q sub_intervalQ9: Div Interval

Alyssa implements division below by multiplying by the reciprocal of

y. Ben Bitdiddle, an expert systems programmer, looks over Alyssa's

shoulder and comments that it is not clear what it means to divide by

an interval that spans zero. Add an assert statement to Alyssa's code

to ensure that no such interval is used as a divisor:

def div_interval(x, y):

"""Return the interval that contains the quotient of any value in x divided by

any value in y. Division is implemented as the multiplication of x by the

reciprocal of y."""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

reciprocal_y = interval(1/upper_bound(y), 1/lower_bound(y))

return mul_interval(x, reciprocal_y)Use Ok to unlock and test your code:

python3 ok -q div_interval -u

python3 ok -q div_intervalQ10: Par Diff

After considerable work, Alyssa P. Hacker delivers her finished system. Several years later, after she has forgotten all about it, she gets a frenzied call from an irate user, Lem E. Tweakit. It seems that Lem has noticed that the formula for parallel resistors can be written in two algebraically equivalent ways:

par1(r1, r2) = (r1 * r2) / (r1 + r2)or

par2(r1, r2) = 1 / (1/r1 + 1/r2)He has written the following two programs, each of which computes the

parallel_resistors formula differently::

def par1(r1, r2):

return div_interval(mul_interval(r1, r2), add_interval(r1, r2))

def par2(r1, r2):

one = interval(1, 1)

rep_r1 = div_interval(one, r1)

rep_r2 = div_interval(one, r2)

return div_interval(one, add_interval(rep_r1, rep_r2))Lem complains that Alyssa's program gives different answers for the two ways of computing. This is a serious complaint.

Demonstrate that Lem is right. Investigate the behavior of the system

on a variety of arithmetic expressions. Make some intervals r1 and

r2, and show that par1 and par2 can give different results.

def check_par():

"""Return two intervals that give different results for parallel resistors.

>>> r1, r2 = check_par()

>>> x = par1(r1, r2)

>>> y = par2(r1, r2)

>>> lower_bound(x) != lower_bound(y) or upper_bound(x) != upper_bound(y)

True

"""

r1 = interval(1, 1) # Replace this line!

r2 = interval(1, 1) # Replace this line!

return r1, r2Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q check_parQ11: Multiple References

Eva Lu Ator, another user, has also noticed the different intervals computed by different but algebraically equivalent expressions. She says that the problem is multiple references to the same interval.

The Multiple References Problem: a formula to compute with intervals using Alyssa's system will produce tighter error bounds if it can be written in such a form that no variable that represents an uncertain number is repeated.

Thus, she says, par2 is a better program for parallel resistances

than par1 (see Q10: Par Diff for these functions!). Is she right? Why? Write a function that

returns a string

containing a written explanation of your answer:

Note: To make a multi-line string, you must use triple quotes

""" like this """.

def multiple_references_explanation():

return """The multiple reference problem..."""

Q12: Quadratic

Write a function quadratic that returns the interval of all values

f(t) such that t is in the argument interval x and f(t) is

a

quadratic function:

f(t) = a*t*t + b*t + cMake sure that your implementation returns the smallest such interval, one that does not suffer from the multiple references problem.

Hint: the derivative f'(t) = 2*a*t + b, and so the extreme

point of the quadratic is -b/(2*a):

def quadratic(x, a, b, c):

"""Return the interval that is the range of the quadratic defined by

coefficients a, b, and c, for domain interval x.

>>> str_interval(quadratic(interval(0, 2), -2, 3, -1))

'-3 to 0.125'

>>> str_interval(quadratic(interval(1, 3), 2, -3, 1))

'0 to 10'

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q quadratic